Previous installments of “The Adventures of Superman” episode guide : Season, 1, Part I – Season 1, Part II – Season 2.

This article originally appeared in a slightly different form at Alfred Eaker’s The Blue Mahler.

Under Kellogg’s sponsorship, the second season of “The Adventures of Superman” had already began steering away from an adult audience. By the third season, the show was aimed almost solely at the pubescent. It was also shot in color, which made it an expensive production, with less money allocated for actors or professional writers. Oddly, it was only aired in black and white, not having its color premier for another decade. In this, Kellogg’s was ahead of its time, realizing that color, being inevitable, would assure the series a long run in syndication.

The third season is an entirely different series than the first two and, with few exceptions, it’s a dreadful affair. The series’ decline continued until its final, sixth season. Although officially cancelled, “The Adventures of Superman” had been picked up for a seventh season with star George Reeves coming in as director (he helmed three episodes late in season six) and, reportedly, more money was going to be spent on better scripts. However, Reeves’ premature death put an end to a series which began high and should have bowed out on a better note. Alas, like its star, it was not afforded a happy ending.

The cast still has charisma, but even they can’t save the worst episodes, many of which are excruciating and virtually unwatchable. Still, “The Adventures of Superman“ (along with I Love Lucy) was the longest running series of the fifties, and maintained its popularity for another three decades in syndication. This is remarkable given that its lead, who presented a Super Boy Scout image, had in fact been outed as quite the colorful character, engaged in a sordid affair when he was found dead, allegedly by his own hand.

The third season opens with the godawful “Through the Time Barrier” (dir. Harry Gerstad). The “Daily Planet” staff (all four of them) are teleported to the Stone Age by Professor Twiddle (Sterling Holloway, in his last series appearance). The look on Reeves’ face speaks volumes.

The third season opens with the godawful “Through the Time Barrier” (dir. Harry Gerstad). The “Daily Planet” staff (all four of them) are teleported to the Stone Age by Professor Twiddle (Sterling Holloway, in his last series appearance). The look on Reeves’ face speaks volumes.

“The Talking Clue” (dir. Gerstad) is marginally better. It’s about a bank robber named Muscles McGurk, and focuses primarily on Inspector Henderson. Robert Shayne enjoys the spotlight, and our enjoyment comes primarily from his.

“The Lucky Cat” (dir. Gerstad) is an engaging, silly story about an Anti-Superstition Society, with Jimmy (naturally) falling for all the Continue reading THE ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN STARRING GEORGE REEVES: SEASON 3-4 EPISODE GUIDE AND REVIEWS

Lugosi fans (and they are legion, or at least once were) are hardly apt to admit it, but their object of adulation was one of the genre’s worst actors, due in no small part to his clear disdain for the English language and astoundingly poor career choices. With damned few exceptions (notably, Ygor in Son of Frankenstein), he was a one-note performer. Even

Lugosi fans (and they are legion, or at least once were) are hardly apt to admit it, but their object of adulation was one of the genre’s worst actors, due in no small part to his clear disdain for the English language and astoundingly poor career choices. With damned few exceptions (notably, Ygor in Son of Frankenstein), he was a one-note performer. Even

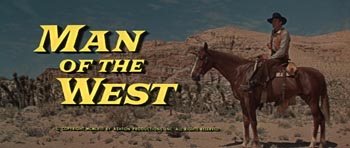

Link Jones is about to catch a train headed for Texas. He is on a mission to find a school teacher for his small town’s new school, and is carrying the funds to pay for her. A Marshall at the local train station thinks he recognizes Link, asks Link his name, inquires into Link’s past, and asks him if he knows the fugitive Doc Tobin (Lee J. Cobb). Link cautiously shakes his head, lies, squints, and evades the Marshall’s penetrating looks. Mann’s expert manipulation of Cooper’s personality traits is so subtle as to be believable and, thus, unnerving. It was unsettling enough for 1958 audiences to reject it, and even contemporary critics have often lamented the casting of Cooper, as opposed to Stewart, in this film. Stewart would not have worked nearly as well, simply because his casting would have been acceptable, even expected.

Link Jones is about to catch a train headed for Texas. He is on a mission to find a school teacher for his small town’s new school, and is carrying the funds to pay for her. A Marshall at the local train station thinks he recognizes Link, asks Link his name, inquires into Link’s past, and asks him if he knows the fugitive Doc Tobin (Lee J. Cobb). Link cautiously shakes his head, lies, squints, and evades the Marshall’s penetrating looks. Mann’s expert manipulation of Cooper’s personality traits is so subtle as to be believable and, thus, unnerving. It was unsettling enough for 1958 audiences to reject it, and even contemporary critics have often lamented the casting of Cooper, as opposed to Stewart, in this film. Stewart would not have worked nearly as well, simply because his casting would have been acceptable, even expected.