(original 1979 cut)

(original 1979 cut)

(Redux cut)

(Redux cut)

DIRECTED BY: Francis Ford Coppola

FEATURING: Martin Sheen, Marlon Brando, Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper, Fredric Forrest, Albert Hall, Sam Bottoms, Larry Fishburne, Harrison Ford, Bill Graham, Colleen Camp, Christian Marquand (Redux only), Aurore Clement (Redux only)

PLOT: Loosely based on the Joseph Conrad novella “Hearts of Darkness,” the film centers on Willard (Sheen), who is sent up the rivers of Cambodia to terminate the mad Colonel Kurtz (Brando) and destroy his cult-like compound.

WHY IT WON’T MAKE THE LIST: Apocalypse truly is the Vietnam war on acid. At times it’s surreal, hallucinatory and mind-blowing, but that’s not always the same as weird. However, if this were a list of the 366 greatest films ever made, it would definitely make it. Heck, Apocalypse would probably make a list if this of the 66 greatest films ever made—although the longer 2001 Redux version is definitely inferior to the original 1979 film.

COMMENTS: Francis Ford Coppola’s original 153-minute version of Apocalypse Now opened in 1979 after a chaotic production and almost two years in the editing room. All that time, money and effort paid off, because, despite a draggy third act, Apocalypse Now is one of the maddest, greatest war movies ever made. Willard’s trip down the river (or the rabbit hole) is punctuated by one mind-boggling set-piece after another, including a helicopter assault on a Vietnamese village scored by Wagner’s “Ride of the Valkyries”, a USO show featuring Playboy bunnies that slowly devolves into a chaotic free-for-all, and an opening sequence where a drunken Willard trashes his hotel room while Jim Morrison’s eerie “The End” pours out in surround sound. It’s the Vietnam War filtered through madness, LSD, and loads of unforgettable music.

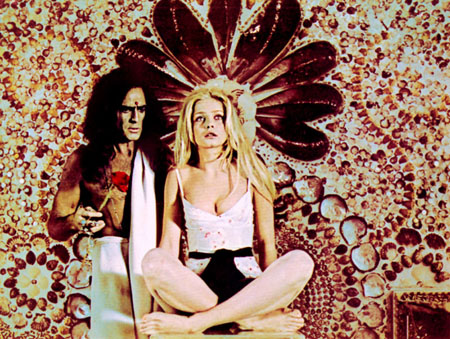

The Redux version of the immortal film adds 49 minutes of frankly unnecessary footage, resulting in a wildly overlong 202 minute film. The “new” sequences mostly consist of two never-before seen set-pieces. In the first, Willard encounters a French family living on a plantation. They’re in Cambodia, but it’s as if they were still back in France circa 1950. Willard even finds romance with one of the women, Roxanne (Clement). This sequence, while interesting in an academic sort of way, is less than compelling. In the second new subplot, Chef (Forrest) and the other men on Willard’s boat spend the night with several of the Playboy bunnies last seen during the memorably disastrous “Suzy Q” sequence. These added scenes do little but show us that Willard and his crew found female companionship on their trip up the river, and it’s easy to see why Coppola cut the footage in the first place. It’s just not that involving.

Luckily, the rest of Apocalypse is still there: every other brilliant sequence that has earned the film a reputation as a flawed masterpiece. Yes, once Brando turns up, the movie sort of slides downhill, but the last 30 minutes improve upon repeated viewings. Furthermore, the 2010 Blu-Ray restores the film to its original widescreen dimensions. All the previous DVD versions had cropped the picture to fit high-definition television screens (according to cinematographer Vittorio Storaro’s wishes), but no more. This Blu-Ray also includes the jaw-dropping 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness, which examines the film’s nearly disastrous 1976-7 production, which was beset by typhoons, a heart attack, and a budget that swelled to a then-staggering $31.5 million. Directed by Eleanor Coppola (wife of Francis), the doc is itself must-see viewing.

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY:

Huston’s direction of Reflections is Flannery O’Connor-like: impressionistic language combined with objective, clear-eyed view of darker themes and people within an exquisitely austere

Huston’s direction of Reflections is Flannery O’Connor-like: impressionistic language combined with objective, clear-eyed view of darker themes and people within an exquisitely austere