366 Weird Movies may earn commissions from purchases made through product links.

DIRECTED BY: Derek Jarman

FEATURING: Steven Waddington, Tilda Swinton, Andrew Tiernan, Nigel Terry

PLOT: Upon the death of his father, Edward II lifts the banishment of his friend and lover, Piers Gaveston; in response, his royal court rebels and civil war ensues.

WHY IT MIGHT MAKE THE APOCRYPHA LIST: Unlike many period pieces, this has homoerotic dance interludes, a serenade crooned by Annie Lennox, and a chilling scene in which Tilda Swinton’s Queen Isabella lustily bites the neck of a disloyal nobleman. But beyond the obvious oddities, Edward II‘s narrative pinches more than flows, its disjointed scenes rendering the film’s array into a garment that juts out in disquieting spikes at the observer.

COMMENTS: To fully appreciate what is going on in Edward II, one must have a decent grip on England’s 14th-century history, 16th-century theatre, and 20th-century cinema. History’s pertinence pools sickly within the bumps and cracks of Derek Jarman’s austere sets, casting its gloomy but far-reaching glow under the director’s harsh lighting. The doomed players—the king and his lover; the queen, and hers—are archetypal tragic figures attired in smart modern dress. Gilded glamor and radiant red splatters the creaking, decaying artifice of the seat of English power as the flawed monarch fights vainly to secure first the safety of his lover, Gaveston, and then his own. Through Edward II, Jarman grinds his axe in the Middle Ages before taking it to the neck of contemporary England.

Three times it is read that Edward II’s father has died, and three times it is read that Piers Gaveston’s banishment has thus been rendered null and void. To the chagrin of all but the new king, Gaveston returns from France, enchanting Edward anew, and infuriating the establishment. Edward sees nothing but beauty in Gaveston, and feels nothing but his love. Edward’s queen, Isabella, feels spurned, and considers self-exile until Mortimer, the commander of England’s armed forces, convinces her that he has a plan. His plan unfolds, and Edward grudgingly banishes Gaveston once more. But the plan folds in on it itself, and the murky doings of the discontented nobles trigger a series of upsets, turn-abouts, and murders.

This is a juicy tale, to be sure, and that juiciness is reinforced by Jarman’s aesthetic. King Edward’s private haven is a square pool of murky water, tucked away in a basement chamber with rusted-steel walls; upon his second banishment, Gaveston endures a gauntlet of spitting nobles; and blood, when it appears, is ample, particularly after the queen renders harmless an erstwhile ally. The lines are delivered wetly, as well. The actors are not slurping and sputtering, but the sound design emphasizes the wetness of the lips, the throaty fullness of exhortations. The slick-slap of words is brought forward in the sound design and rendered at full volume—dialogue delivered in drenched sorrow.

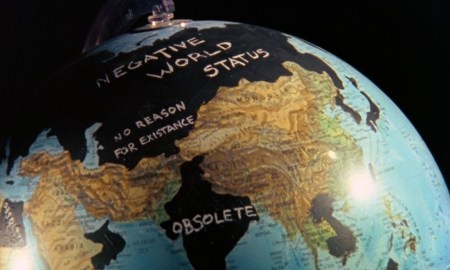

Whether or not the time-jumping anachronism, accentuated performances, and installation-style shots and sets work for you will hinge on whether you are open to the full Derek Jarman experience. An avid gay rights activist, Jarman eschews any ambiguity about the actual monarch, and is willing, able, and eager to toss aside two things: any cinematic conventions that may stand between him and making beautiful, painterly images, and any staid historicism that may stand between him and his proudly gay point of view. It opens with a conversation between Gaveston and a traveler; two men unabashedly make love behind them. It closes with a lament from Edward playing over shots of assembled, real-life gay rights activists. Derek Jarman had a clear world-view, and in Marlowe’s play, he found the perfect framework to display his classically peculiar visual élan while simultaneously preaching his message.

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY: