366 Weird Movies may earn commissions from purchases made through product links.

DIRECTED BY: Tage Danielsson

FEATURING: Gösta Ekman, Hans Alfredson, Margaretha Krook, Lena Olin, Bernard Cribbins, Wilfrid Brambell

PLOT: The life of the legendary Spanish painter, told with a questionable level of veracity.

COMMENTS: In a few weeks, a motion picture will make its streaming debut purporting to tell the remarkable story of pop music’s crown prince of parody, “Weird Al” Yankovic. Weird promises to cover every step of the master accordionist’s life and, whenever possible, to subvert the proceedings with lies and misdirections. It’s a fitting approach for someone who has built a career out of taking familiar sounds and destroying them from within.

What it won’t be is unprecedented. The grand womb-to-tomb biopic has been assailed before. Its conventions have been savagely parodied. We’ve seen lives thoroughly misappropriated with falsehoods and flights of invention. (And that’s to say nothing of legitimate productions that shred the truth to achieve better storytelling.) It turns out that a leading exemplar of the ridiculous film biography hit screens years earlier, the product of a Swedish comedy duo who wondered what it would be like to make an authoritative biography when you have virtually no knowledge of the subject.

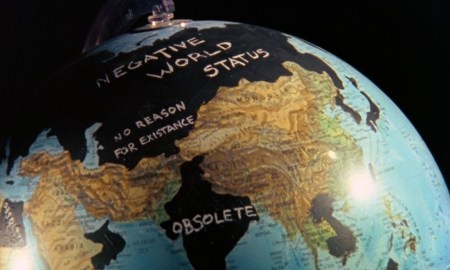

Like a book report by a student who did absolutely none of the reading, this take on the life of Picasso is drenched in flopsweat. Within the first 15 minutes of the movie, the pieces of the Picasso legend are already falling into place: young Pablo has established his bonafides at art school (successfully painting a nude after seeing the model for a split second), relocated to Madrid, adopted his trademark striped shirt and white trousers, and invented cubism. Having burned what few facts they have available, the filmmakers pivot to wildly making stuff up. Did you know that Picasso was gifted with a vial of magical ink by a woman he saved from a pair of foul brigands? Maybe you recall his illustrious contemporaries, who evidently include Ernest Hemingway, Erik Satie, two Toulouse-Lautrecs, Puccini (and his real life Mimi), Vincent van Gogh, and even Rembrandt. And who can forget the real story of how a petty artistic quibble between Churchill and Hitler presaged World War II. (No wonder Picasso would seek refuge in America, despite the notorious Art Prohibition of the Roaring Twenties.) The Adventures of Picasso is the movie equivalent of converting text into Japanese in Google Translate and then back.

One of the film’s most inventive techniques is the choice to dispense with dialogue altogether. Actors speak in grunts and gibberish or spout cursory and irrelevant phrases in pidgin versions of various languages. (A persistent chanteuse sings lyrics that are actually a recipe for a Finnish fish pastry.) Even the headline of the traditional newspaper carrying the word of the outbreak of World War I reads simply “BOOM KRASCH BANG!” Only the narration is necessary to carry the story forward, and you get a different version depending upon your native tongue. (English-speakers like myself are treated to comic actor Bernard Cribbins, in his role as Gertrude Stein.) The filmmakers have thus given themselves an out: don’t understand what’s going on? No worries; you’re not supposed to.

While writers Danielsson and Alfredson will do anything for a joke, they show surprising empathy for the Picasso they’ve created. There’s an extended skit where the onscreen Picasso is forced to do whatever the narrator dictates, and that typifies the notion that Picasso ultimately had no agency, a victim of his own success. His father is a relentless huckster; when his dicey hair tonic instantly produces Picasso’s famous baldness, the old man immediately sells the locks to capitalize on his son’s fame. Throughout the rest of his “career,” dear old dad will be there, making friends with history’s greatest monsters and looking for the quickest way to make a buck. At the end, the great artist is nothing more than an exhibit himself; his home is a theme park and his doves of peace are trinkets to be sold. In this telling, Picasso doesn’t so much die as drop out, leaving our materialistic world behind.

The Adventures of Picasso certainly takes an unusual approach to biography; if you come hoping to learn anything about the creative mind behind “Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon” or “Guernica,” you will surely be disappointed. And even the deeper truth that may be lurking within seems suspect; the real Picasso was far from an innocent and was in full control of his brand. But there’s something almost noble about the notion that if you can’t get it right, then by all means get it completely and utterly wrong. Or, as another great biographical subject once observed, “It doesn’t matter if it’s boiled or fried. Just eat it.”

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY:

(This movie was nominated for review by Ettin, who called it a “[S]wedish surreal comedy” that ” [I]’m sure you will like.” Suggest a weird movie of your own here.)

The scene in which Eva confronts Charlotte throughout the night is lengthy, riveting, and drenched in emotion. Charlotte’s propensity for bragging and her lack of humility, her inability to listen and perhaps even to fully love, is punctuated by Eva’s demand of silence, and, ultimately by her mediocrity. Yet, we also see Eva’s strength as a giving savior/saint to both her husband and sister—a role that Charlotte is utterly incapable of. Lesser filmmakers would have taken sides and painted the scene solely in hues of pathos, but Bergman is not so monochromatic: he uses humor, awe, and sensuality. Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nyqvist opt for intense extreme closeups, filmed in gorgeous oranges and browns. It’s called Autumn Sonata for a reason, and the engrossing music (Chopin, Bach, Beethoven) is of equal importance to the theatrical-like visuals.

The scene in which Eva confronts Charlotte throughout the night is lengthy, riveting, and drenched in emotion. Charlotte’s propensity for bragging and her lack of humility, her inability to listen and perhaps even to fully love, is punctuated by Eva’s demand of silence, and, ultimately by her mediocrity. Yet, we also see Eva’s strength as a giving savior/saint to both her husband and sister—a role that Charlotte is utterly incapable of. Lesser filmmakers would have taken sides and painted the scene solely in hues of pathos, but Bergman is not so monochromatic: he uses humor, awe, and sensuality. Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nyqvist opt for intense extreme closeups, filmed in gorgeous oranges and browns. It’s called Autumn Sonata for a reason, and the engrossing music (Chopin, Bach, Beethoven) is of equal importance to the theatrical-like visuals.