DIRECTED BY: Neil Breen

FEATURING: Neil Breen, Joy Senn, Elizabeth Sekora

PLOT: Jesus visits Earth to fix our energy dilemmas while performing random miracles along the way. It’s that simple, we’re done.

WHY IT WON’T MAKE THE LIST: Did this movie actually get recommended for the whole seven plastic doll heads out on the ground in the desert? Or, wait, was it for the knife soaked in strawberry jam to represent street violence? The Halloween mask that flickers into view a few times? The only way anyone could claim this movie is the weirdest thing they’d seen is if they were literally a fetus watching it from inside a womb somehow.

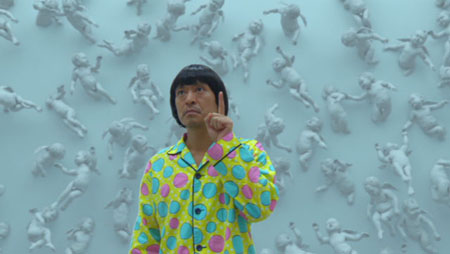

COMMENTS: Holy Tommy Wiseau! This movie was not only written, directed, and produced by Neil Breen, but he plays the lead role in it too, which is apparently his usual mode. And Jesus Christ! No really, Jesus Christ is in this movie, played by Neil. Who is here. Now. So this is a whole vanity project where the creator wants to play Jesus—just try to tell me that we’re not in for a grand old time! Jesus has computer parts glued to him, though, and he lands in the Nevada desert from an incoming comet, so he’s Space Jesus. He angrily shakes a skull (there’s always one laying about when he needs one) while demanding of it why humans have failed him. Yorick doesn’t answer. Space Jesus is really bummed about how humans have turned out. Because we humans sit around drinking beer, getting stoned, and shooting guns, even if Space Jesus happens to be standing in the way. But if you try to shoot Space Jesus, he will take your clothes and truck and drive into Las Vegas, so he can find more things to scowl at. Hope you’re stocked up on your Depends, because the pants-pissing hilarity is just beginning.

While Space Jesus approves of our finally getting the hang of solar power, he’s unhappy about our greedy money-grubbing capitalism slowing progress down and vows to make it go away. So we hear speeches about clean energy vs. greedy business, and then we know what message Space Jesus wants to pound into our stubborn, concrete skulls for the remaining hour. As Big Business shuts down Solar Power, a laid-off employee laments the state of affairs while pushing a baby in a stroller; hopefully this long-winded dialog is not taking too much time out of the baby’s schedule. We follow her predicament for awhile, as her twin sister steers her into being a stripper to support her baby. She sinks into a world of urban depravity right away. In fact, “sinks into depravity right away” is pretty much Team Human’s job in the whole film, because only Team Space Jesus can rescue them with the power of his deadpan pout and Photoshoped glowing hand.

As hilariously somber as Space Jesus is when he’s onscreen, it gets even funnier when extras have to memorize and recite his Wikipedia paragraphs of dialog at each other without a whiff of actual acting, because they are just finger puppets to Neil Breen. Finger puppets who are never allowed to wear bras or button their blouses up, and who lash out in violence at the drop of a jump cut. Really, the supporting cast is the biggest puzzle: none of them, not even the ones who are supposed to be thugs, look like they’ve lived through hard enough times to be willing to be in this embarrassing movie for nothing. They must have been paid in grown-up money, yet not a single one of them puts out a spark of effort. They even scream in lower-case: “don’t cut off my hand. aaaaaaaaaaah.” In every shot with Neil and a supporting cast member, watch their faces as they try not to crack up. Out of all the things Breen’s bad at, scriptwriting is his weakest suit.

The cinematography is competent, letting the desert look beautiful, and this movie at least succeeds at clearly and boldly telling the story it wants to tell (yes, Breakfast of Champions scarred me deep). Any idiot could follow this: it is about Space Jesus the entire time, and at that, it’s a more likable Jesus story than Mel Gibson could produce. Granted, this movie was produced on an architect’s budget (no really, that’s his day job), and Neil Breen is obviously nuttier than squirrel poop. But at least he has a point, one which resonates with every Millennial who joined #OccupyWallStreet. It’s not even that bad; I Am Here…. Now has a tranquil pace and long, quiet stretches, so at least the movie shuts up and lets you reflect on how thankful you are to have moved the hell out of Las Vegas before he started filming random people on the street. Even the soundtrack is relaxing, and doubtlessly royalty-free (stockmusic.net appears in the credits). In sum, Neil Breen is clearly suffering from nearly the same set of mental symptoms that plagued Sun Ra, just without being an innovative jazz musician. Well excuuuuuse him.

Neil Breen does not allow retailers to sell his films. All DVDs must be bought directly from him at either http://fatefulfindings.biz/ or http://www.pass-thru-film.com/. For older movies like I Am Here…. Now, write a note in the comments box when ordering.

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY:

Also see the snarky video review at Cinema Snob.