NOTE: A Serious Man has been promoted from the “Borderline” category onto the List of the Weirdest movies of all time! This page is left up for archival purposes. Please view the full review for comments and expanded coverage!

DIRECTED BY: Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

FEATURING: Michael Stubargh, Richard Kind, Fred Melamed, Fyvush Finkel

PLOT: A putzy Jewish physics professor suffers from an escalating series of problems

including a failing marriage, bratty kids, students willing to do anything for a passing grade, financial troubles, and a ne’er-do-well, mildly insane brother.

WHY IT’S ON THE BORDERLINE: While the early leader for Weirdest Movie of 2009, A Serious Man won’t be eligible to be officially added to the List of the 366 Best Weird Movies of All Time until it receives its DVD release and the film can be pored over meticulously by our team of critics. Okay, to be honest, the home video release requirement is a way to buy time, while I let the Coens’ latest ferment in the back cellar of my consciousness. The conundrum is that, superficially, this movie is not that weird; there are a few dream sequences and nonsense parables, but unlike the Coens definitely weird Barton Fink, this story of a suburban Jewish man beset by an improbably mounting set of real life woes contains no surrealistic fireworks (although there is a conspicuous surrealistic pillow). On the other hand, this movie has a skeletal undercurrent of ambiguity and disturbance running through it like a bone cancer; it feels weird at its core. Also, the way it’s currently unsettling and outraging square moviegoers points to a powerfully different movie.

COMMENTS: A Serious Man is a retelling of that most fascinating parable in the Old Testament, the Book of Job, as a postmodern absurdist comedy. The ancient Job was a good and prosperous man; God allowed Satan to test his faith by wiping out his flocks, killing his children, and smiting him with boils. The beleaguered Job, bothered by visits from three unhelpful friends who try to console him with off-base theological speculations, eventually despairs, but never doubts God’s existence or goodness. His only plea is to understand his misfortune, to be able to ask God directly, “Why me?” God, appearing in a whirlwind, bitchslaps Job for his audacity: “who are you to question me, the Author of the Universe? It’s your job to obey and suffer in silence.” (I’m paraphrasing here). After this reproof, God restores Job’s riches and lets him have new children to replace the ones Satan killed. The author of the book even makes a point to remark that Job’s three new daughters are much hotter than the ones He let get iced.

The Coen’s Professor Gopnik is a more complex and human creation, and definitely a funnier one, than the symbolic Job of the Old Testament. His suburban troubles are minor league compared to the pestilences Job suffered, but they’re easier to relate to: domestic troubles; bratty kids; oppressive legal bills; anonymous letters unfairly smearing his morals; persistent calls from the Columbia record club; and a layabout, unemployable brother living on his couch who spends most of his time in the bathroom draining his cyst. The ex-friend who’s stealing his wife from him—himself a serious man—is insufferably and hilariously unctuous. He adds multiple insults to Gropnik’s injury, giving him bottles of fine wine and big bear hugs as he consoles the loser and calmly designs new sleeping arrangements for the trio. Gropnik’s troubles mount and pile up on one another until he’s losing his mind, when, in desperation, he seeks help from three rabbis, each more obtuse and less helpful than the last.

Gropnik’s frustrated reactions to the absurd plagues that smite him, the indignities he suffers and the impractical advice he gets, are wickedly funny. Not only is the film funny, but it’s also firmly lodged in a lovingly textured, real universe: a Jewish suburban community in conservative Minnesota in 1967. One thing’s certain: this film is so dripping with Judaica, you’ll feel ready to be mitzvahed after just one viewing.

Although we sympathize with Gopnik for his bad luck, he’s more complicated than good guy Job, because he’s such a passive figure. Sure, he’s a family man who observes Sabbath and sends his kids to Hebrew school, but is this enough to make him a serious man? We have to wonder whether his son would place an emergency call to him at his divorce lawyer’s office to ask him to adjust the TV antenna, or whether his wife would be so anxious to leave him for a more serious man, or if he would have gotten in so much trouble with the exchange student who’s trying to bribe him for a passing grade, if he were more assertive. He’s a harmless man who suffers more than he deserves, but might he have brought many of his troubles on himself? He seeks advice and waits for other people to solve his problems for him—even, perhaps, waiting for God to intervene—but could this failure to seize his own destiny be one of the sources of his multiple heartaches?

A seemingly unrelated story opens the film, a chilling fireside tale set in an Eastern European Jewish community about an old man who may or may not be a dybbuk (ghost). The significance of this opening scene is debatable, but more than anything it seems to relate to the “well of Jewish tradition” the movie explicitly calls on as a way to understand suffering. And one of the main features of Jewish wisdom, at least as the Coens present it, is that it’s a tradition that recognizes and even embraces ambiguity and mystery. These stories the Jews tell each other over and over through the ages remind them that they can’t know God’s mind, but must go on and be faithful nonetheless. The second rabbi’s hilariously absurd and seemingly pointless story about the Jewish dentist who finds a message from God on a goy’s teeth hammers that point home. The movie begins with the rabbinical epigraph “Receive with simplicity everything that happens to you.” “Accept the mystery,” counsels another character in the middle of the film (in a deliciously mysterious twist, he delivers this advice like a vessel of God, without actually understanding what he is saying).

There is a fascinating contrast between that opening scene and the rest of the movie: despite the fact that we don’t know if the visitor is a dybbuk or not, the peasant’s wife does. Whether she’s right or wrong about his demonic heritage, she acts, decisively and irreversibly, in a way that her timid modern successor, Gropnik, never could. Right or wrong, her act belongs to her; if she suffers misfortune for her deed, there will be no question why.

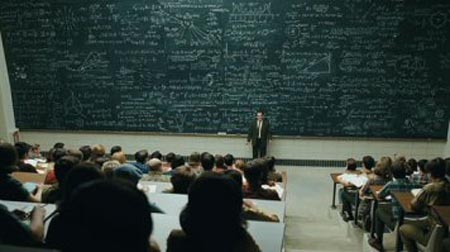

It was a simpler time back in the shetl. Gropnik, a physicist, has bewildered himself by probing deeply into quantum mechanics and the uncertainty at the base of the subatomic particle. It was a stroke of genius for the Coens to make their Job a physics professor, because, like Judaism, modern physics has its own set of inscrutable parables. When a student claims to understand the notoriously difficult paradox of Schrödinger’s half-alive, half-dead cat, an annoyed Gropnik shoots back “even I don’t understand the cat.” But the prof emphasizes that the math behind the paradox works, and that’s what’s important. In physics, at least, he receives with simplicity what happens. That proves to be a harder lesson to apply in real life.

The ending to A Serious Man is already notoriously divisive; some hail it as brilliant, others see it as a cheat, the act of filmmakers without a clue how to end their own story, who just snap the camera off on a cliffhanger. I don’t mind endings that are ambiguous or inconclusive—I adore them when well done—but I have to agree with the detractors that A Serious Man‘s ending is too abrupt. A mysterious image that implies more than it says is a fine thing to end a film on, but the audience should have a chance to savor a building climax before the rug is suddenly pulled out from under them at a seemingly random point. The Coens’ own Barton Fink ended on an even more mystifying note than this one, but that startling image came in an epilogue, after Barton’s final act had already been resolved in our minds. The scene was a weird cherry on top, not the entire dessert.

A Serious Man‘s final image is exceedingly clever when we remember that this is a retelling of the Book of Job. The Coens remember their source, but have deliberately decided to end their tale just before the resolution of the Wisdom book, without giving a comforting answer to the misery but without irreversibly shutting the door, either. That ambiguous ending is thematically consistent in a movie that insists that we can never understand our own suffering from the inside. Prospects look bleak for Gropnik, but we don’t know for sure what happens to him or his family; perhaps he reconciles with his wife and she births him three more daughters, each hotter than his current nose-job seeking brat. But that cleverness doesn’t make us any more satisfied when the scene suddenly cuts to black.

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY:

“Surely some revelation is at hand…”

I find the opening dialogue regarding “the math” to be one of the more revealing pieces in the film.

“You understand the dead cat? But… you… you can’t really understand the physics without understanding the math. The math tells how it really works. That’s the real thing; the stories I give you in class are just illustrative; they’re like, fables, say, to help give you a picture. An imperfect model. I mean – even I don’t understand the dead cat. The math is how it really works.”

And as the film says, the Jews have a tradition of stories to draw upon. In a bit of role-reversal, in that one scene Gopnik becomes the rabbi (more to the point, a kabbalist) to his beleaguered student. What’s the term? As “hysteron proteron,” it’s prototypical for the rest of the film.

Of course, the Coen’s are more interested in the ambiguity of the problem of evil, rather than any definitive answers. What answer would they give anyway? Surely it’s no accident that the final image is juxtaposed with a decision made by Gopnik (accepting the mystery?). Not when the film had explicitly referenced the story of Abraham and Isaac.

“I didn’t do anything!”

“Good riddance to evil!”

Anyway, that is at least one of the things going on. As with any ambiguous tale, this can probably be discussed ad nauseum. I’m fairly certain that the Coen’s have as much knowledge of physics as most fiction writers who like to evoke the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which is to say not very much. I’m also fairly certain they know more about Jefferson Airplane than I do, so who’s to say what’s what?

“Just look at that parking lot.”

Oops! I promoted this one on to the List, but I should have closed comments and directed readers to the expanded review. I’ve moved your comment there, Rob.