In the documentary Looking for Charlie Bowers, film archaeologist Raymond Borde recollects buying a box of silent film reels marked “Bricolo” from a gypsy. Borde was unable to identify the films or the filmmaker, but found the films quite unique. The character in the Bricolo shorts was clearly patterned off of Keaton, but the gags were highly surreal, mixing animation with live action. The search for the identity of Bricolo took Borde to the Belgium Royal Film Library and the Annecy Animated Film Festival. Still, no one could identify the films. Borde searched the exhaustive reviews of “Midi Minuet Fantastique,” which lead to a dead end. Finally, Borde discovered a 1928 reference to Charley Bowers as Bricolo in a “Meric Cinematographers” ad in Mareilles. From there Borden contacted Louise Beaudet of the Montreal Film Library. Beaudet knew Bowers as the animator of the “Mutt and Jeff” series. Together, Borde and Beudet contacted the Library of Congress and struck gold. With much material, including press releases and hundreds of photographs, they were able to positively identify Bowers as the Bricolo of the reels.

Bowers life story proves as fascinating as his films and the discovery of his films. Charley Bowers joined the circus as a tightrope walker at the age of five. From there he worked as a jockey, cowboy, horse trainer, theatrical performer and caricaturist for newspapers. In 1916 Bowers took on the role of producer, opened his own studio, and began producing a series of animated shorts with a small, ragtag team of animators. In 1924, Bowers began producing shorts which mixed live action with animation, casting himself as the lead. Bowers character was called Bricolo by French critics of the time. Bizarre animated objects and puppets were part of the animated sequences.

Borden discovered a late 1930s reference to Bowers by Surrealist Andre Breton. Breton had only seen Bowers’ short “It’s a Bird” as an introduction to a feature film. Breton was surprised by the film and listed it as an important surrealist film in “The Surrealist Almanac.” Borden discovered that Breton’s admiration for Bowers was shared by the avant-garde poet Rafael Alberti.

Bowers died, destitute and obscure, at the age of 57 in 1946, following a long illness. Although he made hundreds of animated short films, along with the live action shorts, only fifteen of his films survive. These were restored and distributed by Lobster Films in France. This indispensable collection of Bowers films is on the two-disc set Charley Bowers, The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius.

Bowers died, destitute and obscure, at the age of 57 in 1946, following a long illness. Although he made hundreds of animated short films, along with the live action shorts, only fifteen of his films survive. These were restored and distributed by Lobster Films in France. This indispensable collection of Bowers films is on the two-disc set Charley Bowers, The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius.

Like all great surrealism, Bowers film are imaginatively and aesthetically provocative. Recurring obsessive themes permeate Bowers shorts. “Egged On” (1926) and “Say Ah-h!” (1928) both feature unbreakable eggs. In “Egged On” Charley is an inventor and has the great idea that unbreakable eggs will make him his fortune and allow him to marry his cousin (!). The Egg Shipping company is interested in his invention so his cousin lets him build his machine in daddy’s barn. Charley builds a huge machine that looks like something out of a Dr. Seuss cartoon. The eggs come out rubbery, so the Egg Shipping Company comed out for a demonstration. Alas, Charley can’t find any eggs; after a desperate search, he finally finds some. Charley lays the eggs on a Model T Ford which incubates them and out hatch baby Model Ts. This is slapstick surrealism at its maniacal best.

“Say Ah-h!” begins with Charley being chased by Cleo the Ostrich. Charley (looking a lot like Harry Langdon here) has stolen Cleo’s egg, and he throws it to his famished employer, who cannot break it. Finally, a farm hand shoots the egg, ruining it. The farmhand orders Charley to produce another egg. Charley feeds Cleo cement mix. Cleo lays an egg. The egg escapes Charley’s grasp and hatches a fully grown cyborg like ostrich. The hatchling wears pants, has a feather duster for a tail and eats everything in sight, including metal objects. The hatchling escapes, scares the hell out of everyone, dances the fox trot to a record and hatches a couple of eggs which produce more baby cyborg ostriches. The title indicates that the surviving reel of “Say Ah-h” is the second part; the first part is lost and the second half, presented here, is badly decomposed.

“It’s a Bird” (1930) also features a metal-eating bird. This is only sound film that Bowers himself appears in. Charley is employed as a “breaker and a loser” at a junkyard. His job is to break up the cars and” lose” the pieces someplace. Charley’s finding his job difficult when he runs out of places to “lose” the car parts, that is, until he hears of a metal eating bird. A local professor tells Charley how to find a metal eating bird, which you naturally find under a rock. The bird looks like a prototype of the dodo bird from a Porky Pig cartoon. A worm volunteers to help Charley capture the bird by getting himself painted up in metal paint. The trap works, and Charley takes the bird back to the junk yard, where it gorges on car parts. The bird lays and egg, and tries to eat its own egg. However, the egg hatches and out comes a Model T Ford. Charley has a great idea: “We will start our own car line!” The bird laughs, “I only lay one egg every hundred years.” The ending is abrupt and surreal.

“He Done His Best” (1926): Charley is an inventor again, with ambitions to get married. His prospective father-in-law puts him to work in the restaurant he owns, but when his co-workers discover Charley is non-union, they all quit. This leaves Charley alone in the kitchen and he accidentally blows up the restaurant in his overworked zeal. To make amends, he rebuilds the restaurant and invents a machine that will do all the kitchen work, from cooking to washing dishes. This allows for all kinds of surreal stop-motion animation, of course. White-gloved mechanical arms slaughter chickens, cook them, bake cakes, open cans of carrots. The machine is a huge success, but Charley finds the guests he is serving are guests at the wedding of his girlfriend to another man, ending the film in a moment of pathos.

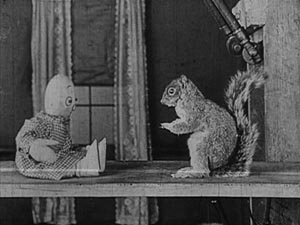

In “A Wild Roomer” Charley is an inventor yet again and stands to gain his late grandfather’s inheritance if he can come up with an invention within 48 hours. If Charley fails, the money goes to Charley’s uncle, who looks like a cross between the classic horror stars Karloff and Lugosi. Again, white gloved arms do all the work, although the purpose of the machine is not really clear, other than perhaps to pamper its owner. The arms make a doll, which comes to life. Amusingly, the doll is embarrassed to find itself naked (shades of Adam and Eve?) and so momma machine makes it a dress. The doll then has a romantic interlude with a squirrel, hops atop it and rides off. Uncle is trying to stop the invention process so that he alone can inherit all the money. Charlie drives the 8 foot high machine (looking even more like Dr. Seuss invention) out into the streets and, naturally, havoc follows. As inventive as the films are, Bowers inability to capture a wider audience is by now quite clear. Bowers was so invested in the animated, surreal gags, that he neglected to develop his own on-screen Bricolo persona in an identifiable way, like Chaplin, Keaton and Langdon did.

In “A Wild Roomer” Charley is an inventor yet again and stands to gain his late grandfather’s inheritance if he can come up with an invention within 48 hours. If Charley fails, the money goes to Charley’s uncle, who looks like a cross between the classic horror stars Karloff and Lugosi. Again, white gloved arms do all the work, although the purpose of the machine is not really clear, other than perhaps to pamper its owner. The arms make a doll, which comes to life. Amusingly, the doll is embarrassed to find itself naked (shades of Adam and Eve?) and so momma machine makes it a dress. The doll then has a romantic interlude with a squirrel, hops atop it and rides off. Uncle is trying to stop the invention process so that he alone can inherit all the money. Charlie drives the 8 foot high machine (looking even more like Dr. Seuss invention) out into the streets and, naturally, havoc follows. As inventive as the films are, Bowers inability to capture a wider audience is by now quite clear. Bowers was so invested in the animated, surreal gags, that he neglected to develop his own on-screen Bricolo persona in an identifiable way, like Chaplin, Keaton and Langdon did.

In “Now You Tell One” the Liars Club is having an annual get together. One member tells of elephants on the Capitol building, and the stop-motion animation for this looks like something akin to Ray Harryhausen to come. However, the lies lack imagination, so a senior member goes out in search for a great liar. He finds Charley trying to blow his head off in a cannon. Charley is taken back to the club. He is introduced as Bricolo, so great a liar that even the King of the Gullible would never believe him. Charley tells the club how he invented a potion that will graft together any two objects and make them grow. Pineapples and apples grow into a combined plant, as do cucumbers and squash, straws change into a hat, seeds into shoelaces, and the handle of a wheel barrel grows a Christmas tree. Charley happens upon a pretty girl with cute legs who is stressed out over a huge problem with mice. Charley grows her some cats, but like the sorcerer’s apprentice, the magic gets away from him and soon her house is overrun with cats.

In “Now You Tell One” the Liars Club is having an annual get together. One member tells of elephants on the Capitol building, and the stop-motion animation for this looks like something akin to Ray Harryhausen to come. However, the lies lack imagination, so a senior member goes out in search for a great liar. He finds Charley trying to blow his head off in a cannon. Charley is taken back to the club. He is introduced as Bricolo, so great a liar that even the King of the Gullible would never believe him. Charley tells the club how he invented a potion that will graft together any two objects and make them grow. Pineapples and apples grow into a combined plant, as do cucumbers and squash, straws change into a hat, seeds into shoelaces, and the handle of a wheel barrel grows a Christmas tree. Charley happens upon a pretty girl with cute legs who is stressed out over a huge problem with mice. Charley grows her some cats, but like the sorcerer’s apprentice, the magic gets away from him and soon her house is overrun with cats.

In “Many A Slip” (1927) Charley is trying to invent the no-slip banana peel. He finds there is a slipping germ which causes banana peels to be slippery. Another machine and additional chaos.

The rest of the films in this collection are lesser entries. These include some live action animated shorts, purely animated shorts, and stop-animation shorts. Oddly enough, Bowers greatest film is possibly “There It Is” (1928), which was not included on this set, but has to be purchased separately within the “More Treasures from the American Film Archives” (which you will probably have to take out a second mortgage just to purchase). Of course, there had to be a snag, and even Bowers posthumous legacy is at the mercy of 21st century marketing strategies that try to squeeze every penny of out collectors. That complaint aside, Charley Bowers, The Rediscovery of an American Comic Genius is a “desert island” collection.

Wow! This sounds absolutely fascinating. The back story reminded me of a novel by Ramsey Campbell called The Grin Of The Dark, but without the supernatural elements.

I have never heard of Charley Bowers, but on the strength of your review I’m off right now to see if I can a)find a copy of this and b) afford it. Thank you Alfred.

Informative. Thanks for the details.

Great article, we all love Bowers! Do you know the source of the André Breton commentary on him? Would be great to have…

I gather from the context Breton’s reference comes from the 1950 Surrealist Almanac [Almanach Surrealiste du Demi-Siecle]. It doesn’t look like something that would be easy to get your hands on.

Have owned this collection for years and watch it often…It’s a Bird and Say Ah-h! are absolute classics in my book.